Did a German Adventurer Discover Machu Picchu Before Hiram Bingham? An Interview with Paolo Greer (Part 2)

posted on August 4th, 2008 in Andes Mountains, Archaeology, Did a German Discover Machu Picchu?, Incas, Machu Picchu, Peru, Recent Discoveries

AN INTERVIEW WITH PAOLO GREER (PART 2)

(To read Part 1, click here)

7) You recently published an article in the “South American Explorer” called “Machu Picchu before Bingham.” In the article you make a number of claims, among them that a German, Augusto R. Berns, purchased an estate called the “Cercado de San Antonio,” or “Torontoy,” in 1867 and that… this estate stretched for 25 kilometers along the northern bank of the Urubamba/Vilcanota River, which would be opposite Machu Picchu. Do you know who Berns purchased this estate from?

PG: Augusto Berns wrote that he had purchased his estate from a Mr. Angulo in 1867.

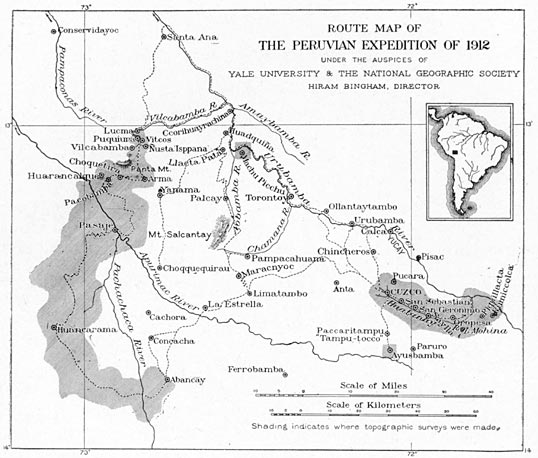

Berns’ property covered nearly one hundred and fifty square miles, one-quarter of the entire Urubamba province. However, his base camp was where the village of Aguas Calientes now lies, just below Machu Picchu.

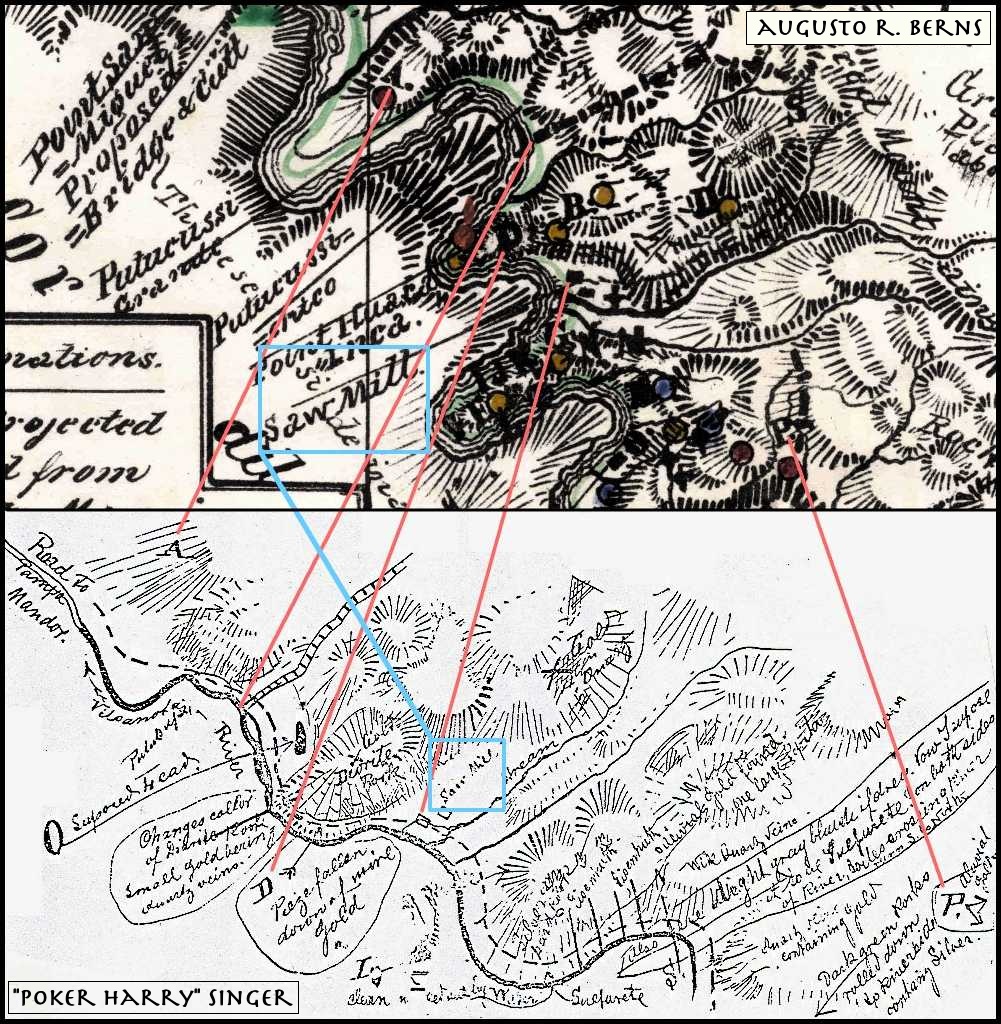

Hiram Bingham’s Map of his 1912 Explorations near Machu Picchu

Berns first arrived at the location of what is, today, a bustling tourist town (the official name of the community is “Machu Picchu Village”) eight years before Hiram Bingham was born, and more than four decades before Bingham was led up to the nearby ridge by [the local Peruvian farmer] Melchor Arteaga.

Who was Augusto R. Berns? Do you have information on his birth or death or where he was from in Germany, in what year he died, etc.? Any personal information at all?

PG: Berns was born in Germany in 1842.

However, I have a tough enough time with my own idiom, and genealogy in German defies me completely. I am hoping that, after the recent release of my article in the South American Explorer magazine, other more fluent researchers will fill in the plentiful gaps about Berns’ early life.

Augusto R. Berns turned up in South America in 1863. In 1881, he stated that he had formerly been a “colonel of artillery in the Peruvian service”, “well known for his successful operations as a military engineer and chief of artillery in 1866, and afterwards as a civil engineer under John Thorndike, C. E., the contractor of the Cuzco-Puno Rail Road.”

In 1867, Berns purchased an “eighteen by eight mile square” track of land on the Vilcanota River, opposite of Machu Picchu.

In June 2008, as a favor to a mutual friend, Alex Lusty, I introduced myself and my pre-Bingham Machu Picchu research to Alain Gioda and Carlos Carcelén in Lima, Peru. According to their story in [El Comercio’s] SOMOS a few weeks later, the two historians have since uncovered accounts about Berns in some late 1880’s newspapers.

SOMOS wrote that President Cáceres’ official permission for Berns’ company to sack the ruins was posted in El Comercio on November 23, 1887; one ‘Christian Dam’ took out an entire page in the paper denouncing Berns; Agustinian priests “very possibly arrived to Machu Picchu” and even established something called “The Picchu Doctrine”; and that I have seen some catalog in a North American library of items that Macedo and Berns removed from the zone.

All this was news to me.

Although I burned CDs of my research for Gioda and Carcelén, so far, my repeated requests for details about these and other revelations have not been answered.

I have worked alone on this project for many years, while sharing what I found with anyone who seemed interested. Naturally, I would be eager to learn what someone else has come up with.

9) You also state that the rusty, iron wheels that Hiram Bingham saw in 1911 at “La Maquina,” a camp along the Vilcanota River, were part of a sawmill operation that Berns established in order to produce railroad ties for the Southern Peru Railroad. How do you know that Berns produced railroad ties for the Southern Peru Railroad? And how did he get the railroad ties out of the area, since this was before there was a road along the Vilcanota River?

PG: I doubt that Berns produced many, if any railroad ties but I give him kudos for trying.

At the time he purchased his property, Berns claimed the mule trail was much improved down the Vilcanota Valley, at least as far as his sawmill.

Berns stated in his “Particulars of the Torontoy” “the new railroad now in progress between Cuzco and Juliaca wants 800,000 ties on the road besides 200,000 for stations.”

He hoped to haul the ‘sleepers’ or ties out and sell them for $3 apiece. To accomplish this, Berns purchased a sawmill, the same one that Hiram Bingham observed near Machu Picchu, “from a Mr. John Gibbon of New Jersey for $20,000.”

By 1881, the sawmill no longer functioned and in 1911, when Bingham made it to what we now know as Aguas Calientes, a place the locals then called ‘Maquina’ [“machine”] because of Berns’ ‘machine’, or sawmill, Bingham thought the rusted hulk was a discarded sugar cane press.

10) You mention that, during a search on the internet, you learned of some papers the heirs of an American backer of Berns had put up for sale. You mention that “the documents contained Bern’s prospectus and a detailed plan of the Torontoy estate that he had made himself.” Did you obtain these materials? And who was the American backer of Berns? Did his heirs know Berns’ story?

PG: My Berns material came in various forms and from several archives.

In the years before internet search engines functioned well, I constantly looked for anything on pre-Bingham Machu Picchu and got zip, until March of 1998 when I located a blurb about three maps and some papers of Berns that a bookseller was offering for sale.

Nearly a decade earlier, in November of 1987, Dan Buck had contacted me to ask for my help concerning a book he was researching on Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid. Buck read an article I’d written about my experiences prospecting in the jungles of southeastern Peru and was trying to trace down a “persistent story” about Butch and Sundance robbing a remote, long abandoned mine that I happened to know well.

It was a great tale about two Gringo banditos who made off with the payroll of the mine and easily held off dozens of pursuers. One was British, but so were Butch’s folks, and he had good reason to affect an accent. Something that also got my attention was one of the outlaws was still alive in Bolivia twenty years later.

Eventually, I was able to track down the original mine correspondence concerning the robbery which unfortunately predated the fugitives arrival to South America by only a few months.

During one of my numerous trips from Fairbanks to Washington D.C., Buck invited me over. It turned out that he had been in the Peace Corps in Peru in the 1960’s and knew some close friends of mine in the town of Puno.

For many years, Buck was a Congressional researcher at the Library of Congress with ready access to the best archives in the world, an advantage that, for a fellow living in an isolated cabin in Alaska, seemed rather astounding.

He was also well paid for his work and had the best personal Latin American library I’d ever seen. Buck was constantly on the lookout for new acquisitions for his collection and asked me to let him know if anything came up.

So, when I found the Berns’ papers for sale, I offered to let him buy the originals, if he would simply send me a copy. That batch of Berns materials only cost $50 but reproductions were all I really needed and I considered Buck a friend.

The documents contained an original of Augusto Berns’ handmade map of the vicinity of Machu Picchu, two other smaller scale plans and his five page 1881 prospectus, titled “Particulars of the Torontoy or Cercada de San Antonio Estate”.

Berns had different backers from the States but it is not clear how much they contributed. Among them were George Mahon, Silas Farmer and John Nystrom. Berns wrote that he depended on Mahon for “literary finesse”.

I have no evidence about how much their heirs knew of Berns.

11) What did Bern’s note saying that “I make by hand after a good yellow gumi gusty color” mean? What did he mean by “These points more distinct. This is a small work of some hours and will make all falling in the eye at once. Also makes an elegant map”?

Berns depended on others to brush up his written Spanish or English. When he described his “good yellow gumi gusty color… elegant map”, he was simply waxing poetic about his handy work in his own words.

His sketch was rather crude by modern standards but, by comparing it to numerous other maps, aerial and satellite photos, certain things really did ‘fall in the eye at once’. Berns’ map was very telling.

12) You refer to the map of the Torontoy area that Berns made as a “treasure map.” Why do you call it that?

Mark Twain was once taken by a gold promoter and, afterwards, referred to a mine as, “A hole in the ground with a liar standing next to it.”

Augusto Berns peppered his ‘gumi gusty’ drawing with ‘distinct points’ that he pretended were gold mines.

Simply put, Berns sold dreams, or rather false promises.

13) What you published in the SAE article is just a section of Bern’s map, is that correct? How large an area does the original map cover? And why have you not published it?

PG: And therein lies a tale best left untold, if possible …

Berns’ entire map encompassed “the District of Ollentaytambo [sic], and Province of Urubamba, of which province the estate constitutes about one fourth part,” a region covering 25 by 15 miles (40 x 25 kilometers).

Yet, his camp for many years sat almost exactly where the Aguas Calientes shuttle takes off for the short trip up the hill to Machu Picchu.

In 2003, Jorge Flores Ochoa noticed Herman Göhring’s map of this same area in a Lima museum and told Mariana Mould de Pease. I saw Mould’s write up about it in a Cusco newspaper and contacted her.

I had found the same map in 1989 while researching in Peru’s National Library and passed out a couple hundred copies to historians, archaeologists, folks at the Peruvian National Cultural Institute and about anyone who would hold still long enough to accept it.

Incredibly, no one gave it much notice, even though the map was dated 1874 and clearly showed “Macchu Picchu” and “Huaina Picchu”.

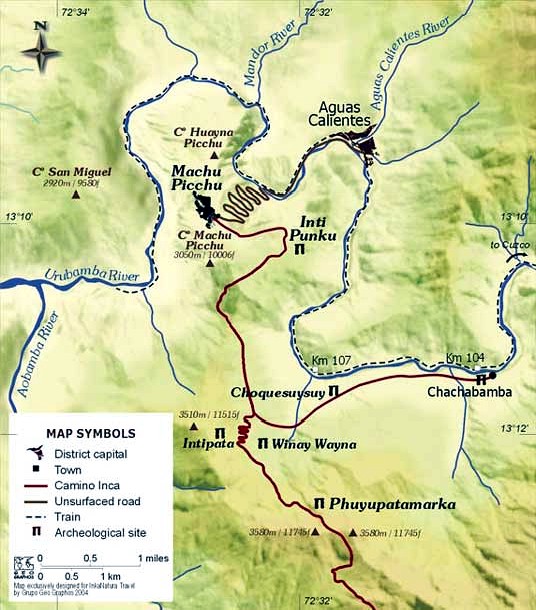

Herman Göhring’s 1874 Map of the Machu Picchu Area

That same year, 1989, I also sent the Göhring map to Dan Buck who eventually put it in his 1993 article, “The Fights of Machu Picchu” in the South American Explorer magazine. In 1999, a Cusco magazine, Via Lactea, also published the copy I gave them.

I have read numerous claims about who first put Machu Picchu on a map but, so far, I have seen nothing that predated Göhring.

There’s a catch though.

The “Macchu Picchu” on Göhring’s map was a peak, nothing more, even if Mariana Mould and others have repeatedly claimed otherwise.

Years ago, I gave Mould a copy of Göhring’s entire 1877 book and showed her his citation referring to the ‘fort of Picchu’.

Still, the Machu Picchu on Göhring’s map, like those of Raimondi and Markham, afterwards, was only a ‘cerro’ or a ‘hill’.

In the late 1860’s, Berns tried and failed to sell railroad ties. Then, based at “Maquina” or “Saw Mill”, he explored the region for years, guided by locals whose families had lived in the area for generations.

In the meantime, Berns promoted phony gold mines in close proximity to his camp and that, more than anything, is my problem with releasing his map, as it should be for anyone who honestly cares about the sanctity of Machu Picchu.

Berns littered his drawing with false mining claims, a stone’s throw from probably the greatest archaeological site in our hemisphere. I was and still am convinced that if the tabloids pick up on this nonsense, they might start a gold rush to the Machu Picchu Reserve, simply to sell a few papers.

For that reason, although I gave Mariana Mould de Pease enough of Berns’ map to convince her that his ‘huaca del Inca’ was indeed Machu Picchu, I refused to give her the entire map, something that she still complains about (she has enlargements of both Göhring’s map and the clip I gave her of Berns in the Machu Picchu museum, crediting herself).

When, instead of buying it myself, I let Dan Buck have the original map and simply send me a copy, he also forwarded a reproduction to Federico Kauffman Doig in Peru, and some big mouth Alaskan Sourdough [that is, P. Greer] let slip to Mould that he had it.

At first, Mould told me bluntly she wanted nothing to do with Kauffman Doig, but she also wanted Berns’ entire sketch and I would not give it to her.

So, to get it, Mould initiated a series of emails, copied to me, President Toledo, the First Lady (Eliane Karp), Mould’s friends in Congress, her powerful media contacts, et cetera, until Kauffman Doig finally sent her a copy of what he had received from Buck.

I had explained to Mould many times why I thought it dangerous to publish this false ‘treasure map’ of Machu Picchu but she insisted that, if she did not do it first, someone else would.

14) Because it is difficult to see this map clearly in reproduction, it appears that Berns has drawn a line above the sawmill that says “Point Huaca del Inca” and that these ruins or “Idol of the Incas” are across the river from Machu Picchu. Is this correct? If so, what ruins do you think Berns was indicating here?

PG: On his map, Berns sketched “Point Huaca Inca” almost exactly where the bridge now crosses the Vilcanota/Urubamba River for the brief walk or ride up the hill to Machu Picchu.

Although I am fairly sure Berns had been picking at Machu Picchu since the late 1860’s, the jungle would have defeated his efforts without a large scale investment.

In June of 1887, Berns received official permission from President Cáceres to excavate his “huacas incásicas” [sic]. A month later, the German announced his enterprise, the “Compañía Anónima Explotadora de las Huacas del Inca” to sack the ruins.

It is no coincidence that Berns’ 1881 map bore the name “Point Huaca Inca” in a spot that had no ruins, save if one stands there now, Machu Picchu is directly opposite and in plain view.

If Berns had chiseled his name in meter high letters across the face of the Sun Temple in Machu Picchu, perhaps the skeptics would be able to make the connection but, then again, maybe not.

15) You say that Berns has written that these ruins are “inaccessible.” Where has he written that?

PG: Until he got official permission to loot the Inca tombs, Berns was tight lipped about the location of what we now call Machu Picchu.

He did not say the ruins were inaccessible. He wrote that the entire side of the river opposite “Point Huaca Inca” was “inaccessible,” which implies that he wanted to discourage others from going there (see Berns’ map [below] where I have highlighted his sawmill [in orange], “Point Huaca Inca” [in red] and “inaccessible” [in yellow]).

Incidentally, I think Augusto Berns deliberately excluded the “cerro” Machu Picchu from his map, even though it was a prominent sugarloaf less than two miles from his camp. Likewise, to protect his looting grounds, he left out the extensive ruins on his doorstep.

Göhring, who investigated and dismissed the false mineral prospects that Berns was promoting, placed “Macchu Picchu” and “Huaina Picchu” in bold letters on his own map from the same years.

However, according to Göhring, the two “picchus” were somewhat reversed from what we know today, and I think he was partially correct.

What millions of tourists have thought of as Huayna Picchu, Göhring marked as “Macchu Picchu.”

I believe the German got that from the locals because the name of the sugarloaf had survived from ancient times; that is, the “picchu” or peak we call “Huayna” was actually Machu Picchu (i.e. “old peak”) to the Incas.

What Göhring marked as “Huaina Picchu” (“young peak”) was mistaken though.

The second outstanding sugarloaf, exactly opposite the river from Machu Picchu, is what is presently known as “Putucusi” (this is the same peak from which private concessionaires recently had intended to build a cable car to cross the river to Machu Picchu).

This significant feature on Göhring’s map was called “Media Naranja”, a newer Spanish name replacing the old Inca/Quechua one.

Berns did include “Putucussi Grande” and “Putucussi Chico” on his plan but they were other mountains, just downriver.

I have always believed that, no matter how many foreigners (or Peruvians from Lima or Cusco, for that matter) say they “discovered” Machu Picchu, the locals never forgot the ruins. Apparently, they also remembered the ancient names of the two amazing picchus or sugarloafs.

Since the modern Putucusi was already known as Media Naranja when Göhring arrived on the scene, he attributed the name “Huaina Picchu” to a less significant hill directly across the river from Berns’ camp. There was another reason why these sugarloafs were so important. In fact, they were probabaly why Machu Picchu was built where it is.

Pachacuti, the ninth Inca, lived a long life and died the same year that Francisco Pizarro was born, before the Spaniards even knew the New World existed.

Pachacuti was the seventh son of the Inca Viracocha. Yet, in his Father’s time, the Inca people were only a tribe, confined to the Cusco valley.

When the Chancas arrived to conquer the Inca people, Viracocha and Pachacuti’s six older brothers fled.

Pachacuti stayed, successfully defended Cusco and went on to become the Genghis Khan of the Incas.

It was Pachacuti, who became known as the “World Changer”, and his son, Topa Inca, who advanced the Inca Empire more than all their ancestors or descendants, together.

Pachacuti also built Machu Picchu.

Before that, the “World Changer” built the Coricancha, the most sacred building in the Empire. At the same time, he placed a large stone, a sugarloaf, in the center of the main plaza of Cusco.

Like Pachacuti, the stone stood for the sun.

In fact, I believe that this sugarloaf and others, like the two “picchus,” as well as the intihuatanas at Machu Picchu (there is a second one in the Royal Mausoleum below the Sun Temple) came to represent Pachacuti himself.

Putucusi, what Göhring called “Media Naranja”, was the Incas’ Huayna Picchu or “young peak”.

Those two outstanding “picchus” or sugarloafs were probably why Machu Picchu was constructed where it is, in deference to Pachacuti, the “World Changer”.

As for “Machu Picchu”, read the 32nd chapter of Juan de Betanzos’ 1557 “Narration of the Incas” (see my article, “Machu Picchu before Bingham”, elsewhere in this blog).

The ancient name for what we know as Machu Picchu was “Patallacta” or “High City”.

16) How do you know that the sketch of the sawmill area that you found in the Library of Congress in 1978 was made by Berns’ partner, Harry Singer? Is his name on it?

PG: There are no dates or anyone’s name on the map.

That particular sketch befuddled me for twenty years–an old, hand-drawn diagram in English, showing the side of the Vilcanota River directly opposite of Machu Picchu.

It was obviously done by someone with mining experience, certainly more than Berns had. Like his map, it showed the same stretch of river and had a “Saw Mill” at its center. Nevertheless, it was written in a different script.

There were also indications on both maps highlighting certain features, the same letters in the same positions (see my graphic [below and with a larger version at end of article] of the two maps compared).

17) Do you know when this map was created?

PG: Berns and Singer went north to avoid the 1879-1883 War of the Pacific, between Peru, Chile and Bolivia.

On the 28th of January of 1882, Berns wrote from Panama, “Here had been shot Mr. Singer about 4 weeks ago as he had drunk together with some Italians, etc., insulting each other and so they shot him.”

So, the map was created before that.

Earlier, in October 1881, Berns wrote that Singer had been setting up flumes near their camp, just below Machu Picchu.

Singer probably drew his map of the area around Berns’ camp in 1881.

18) Where did you find the information about Berns’ partner, “Poker Harry Singer?”

PG: The largest collection of Berns’ papers I found was nearly 300 items (“letters, plans, drafts of advertising brochures, maps and drawings”) stuffed in a cardboard box in the Biblioteca Nacional de Perú.

At first, the BNP denied the papers existed, since there was nothing about such ephemera in their catalog. Then again, the California State University Library at Fresno said differently.

I had originally discovered the brief citation for the “promotional materials relating to an attempt to exploit a mineral area of Peru, 1881” in a 1978 directory of archives. I also found that the collection came from a descendant of one of Bern’s backers and had been purchased from a dealer in 1972.

Later, the California State (now Madden) Library, purged their shelves of non-relevant materials and donated the papers for Berns’ “Torontoy Estate” to the National Library of Peru in Lima.

I persisted and, eventually, turned up the Berns material at the Biblioteca Nacional. When I did, the librarian expressed his incredulity that I was right since the BNP really had no record of it. The material had simply been forgotten, if it had ever been noticed at all.

What I had stumbled upon were twenty-four folders of Berns’ personal papers that had been used by mice to make their nest and stunk of droppings and bookworms.

Among the historical treasures the box contained was a sample certificate for “The Incas Mines Gold & Silver Mining Company 187-“, a drawing of Berns’ camp, seven handwritten drafts of the ‘Particulars of Torontoy’, Berns’ detailed advertisement to sell his property, each different and “improved” upon the last, pieces of metal that Berns has sent to Mahon and numerous letters from Berns.

In one, he spoke of his mother and wife. In another, he mentioned that he had copyrighted his map so that newspapers would not publish it.

Berns also wrote of a [Mr.] Singer of Boston, known in California as “Poker Harry”, who had studied chemistry for six years at Göttingen University in Germany.

(Upcoming: Part 3 of “An Interview with Paolo Greer”)

(Below: Greer’s Comparison of Harry Singer’s and Berns’ Maps)