The Last Days of the Incas’ Peru Tour #4 (Lima)

posted on May 24th, 2008 in Incas, Lima, Peru, Peru, The Last Days of the Incas' Peru Tour

Lima (1 Day) The Plaza de Armas, Francisco Pizarro’s Statue, Pizarro’s Remains, Cerro San Cristóbal

Visiting San Cristobal Hill (Cerro San Cristóbal), where the Inca General Quiso surveyed the battlefield before his defeat.

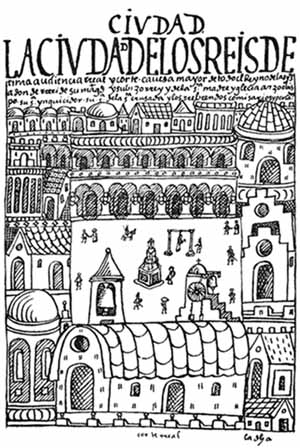

It was here, on top of Cerro San Cristóbal, which juts above downtown Lima, that the Inca Emperor Manco Inca’s finest general, Quiso, surveyed the fledgling town of Lima (shown at left in a drawing by the 16th century Peruvian artist, Felipe Huamán Poma de Ayala) in 1536, prior to his all-out assault on it.

Trapped within it was Francisco Pizarro and about 100 of his men, along with some thousands of coastal and other natives who had sided with the Spaniards. General Quiso was fresh from recent victories—he had just wiped out four columns of Spaniards in the Andes, almost to the man. The Inca Emperor Manco Inca had just rewarded him with his own sister as the general’s new wife, and with a high status litter upon which the general was now carried…

(At left, San Cristobal Hill with the statue of Francisco Pizarro in the foreground)

To quote from The Last Days of the Incas (chapter 10):

“Calling for an assembly of his captains, [General] Quiso waited patiently for them to arrive. From the heights of Cerro San Cristóbal, the general could look out over the city and could see the Inca roads stretching north, east, and south while to the west lay the dull, metallic-blue ocean enveloped in fog. To the east rose the Andes, but only their flanks were now visible due to the constant mist. Gradually, Quiso’s captains arrived on their litters, resplendent in their cotton or alpaca tunics, their colorful mantles, and with their various ornaments of gold, silver, and copper. Once they had assembled, Manco’s general stood and gestured down at the Spanish settlement, announcing gravely that he was “determined to enter the city and take it by force or to die in the attempt.” “I intend to enter the town today and kill all the Spaniards who are in it,’ Quiso said, the golden plugs in his earlobes glinting as he turned. “…Those who accompany me must go with the understanding that if I die, all will die, and if I flee, then all will flee.’ The Indian captains and leaders swore to do as he said….”

Having learned no doubt from his spies that the Spaniards had their own women in the city, Quiso now promised his captains that he would distribute the women to them as gifts, so that the two races could mate and “produce a strong generation of warriors.” The general also reminded his captains that if they were successful, then the hated invaders’ last toehold on their sacred coast would be smashed, and that Tawantinsuyu, (land of) the four quarters, would soon be free of the false viracochas from across the seas. Later that afternoon, after the captains had returned to their troops and on the sixth day of the siege, General Quiso launched his final assault on Pizarro’s City of the Kings.”

“The entire [native] army began to move with a vast array of banners, from which the Spaniards recognized the determination and will they were coming with,” wrote one chronicler. “The Governor [Pizarro] ordered all the cavalry to form into two squadrons. He placed one squadron under his command in ambush in one street, and…the other squadron in another. The enemy was already advancing across the open plain by the river. They were very magnificent men, for all had been hand-picked. The general [Quiso] was advancing in front of them, wielding a lance.”

One of the differences between Inca and Spanish methods of warfare was the fact that among the Incas, the general and his field commanders often led the charge. The typically polyglot selection of native troops, apparently, were accustomed to being led and inspired. As long as they could see their commanders riding on their litters besides or ahead of them, the natives fought with determination. If their commanders went down under enemy maces or sling fire, however, then their attack would often falter. The Achilles’ heel of Inca warfare, therefore, was the placement of the command center of their assaults often at the very apex of their attacks. Spanish commanders, by contrast, normally directed their battles from a position at the rear. Except in the capture of Atahualpa, for example, Pizarro had always sent others—Diego de Almagro, Hernando de Soto, or other captains—to lead the advance. If something should have happened to them, Pizarro always knew, then he would have still remained in full control of the invasion.

[General Quiso] crossed both branches of the [Rimac] river in his litter. Seeing that [the enemy warriors] were starting to enter the streets of the city and some of Quiso’s men were moving along the tops of the walls, the [Spanish] cavalry charged out and attacked with such great determination that, since the ground was flat, they routed them instantly. The general [Quiso] was left there, dead, and so were forty commanders and other chiefs alongside him. Although it seemed as if our men had specially selected them, they were killed because they were marching at the head of their men and thus they were the first that the Spaniards smashed into. The Spaniards continued to kill and wound Indians as far as the foot of the hill [of San Cristóbal], at which point they encountered a very strong resistance from a defensive site they had made.

Night began to fall on a battlefield littered with native bodies and with the bloodied and torn litters of the fallen Inca commanders. The next morning, the Spaniards awakened and found that the entire native army had disappeared as suddenly as it had arrived. Crushed psychologically by the loss of their general and of so many of their leaders, Quiso’s troops had retreated back to the Andes where they no doubt felt more secure. Once again, armored Spanish cavalry–given plenty of room to maneuver–had proven to be the decisive factor. That, coupled with Quiso’s fatal strategy of placing himself and his commanders in the vanguard, had stopped the Inca assault on Pizarro’s coastal city quite literally dead in its tracks.

Three days after Quiso’s death, a breathless chaski runner arrived at Ollantaytambo to Manco’s camp. The emperor sat with a grim face as the chaski repeated a message carried by more than sixty different relay runners about the recent disaster on the coast: General Quiso’s seemingly unstoppable string of victories had ended; the general to whom Manco had just presented his sister as a wife, was dead–and so was a long list of fine Inca commanders; Quiso’s army had retreated in disarray back into the mountains, Manco was told. The Spanish city had not been overrun. Francisco Pizarro was still very much alive, his cavalry intact.

For Manco, the news of Quiso’s defeat was devastating. The empire’s finest general, upon whom so many of his hopes had been pinned, had been destroyed. Whether Manco realized it or not, however, he himself was responsible for Quiso’s death. Encouraged by his general’s seeming invincibility, and perhaps also due to sacred omens or to the advice of oracles, Manco had sent his victorious general on a suicide mission. The Inca emperor had apparently ignored the fundamental reason for Quiso’s prior successes—the effective use of Andean topography to neutralize the dreaded Spanish cavalry—and instead had ordered him to attack on a wide open plain where that same cavalry could not be stopped. Quiso’s final, desperate charge calls to mind the much later Confederate charge at Gettysburg, the Australian assault on Gallipoli, the Charge of the Light Brigade, or any other number of hopeless military endeavors. No doubt, Quiso himself must have known that he had been ordered to carry out a mission that would very likely result in his death. Yet under the direct order of his divine emperor—Quiso had had no other choice than to attack.

Inca tradition had further imperiled Quiso’s final assault by ensuring that the Inca general would have a front row seat when the stakes were at their highest, riding on one of the finest litters in the empire at the very point of the attack. Some Spanish accounts stated that General Quiso was ultimately felled by a harquebus bullet, others that he had died from a lance plunged directly into his heart. No matter. The great warrior was dead, and with him died Manco’s finest military commander—the only Inca general who had thus far managed to successively defeat the Spaniards. With Quiso’s army now in disarray, Manco was no longer in a position to prevent Pizarro’s cavalry from riding in relief of Cuzco. Manco was about to receive even worse news, however: a column of four hundred, fully armored Spanish soldiers was on its way back to Peru—and riding at its head was Pizarro’s one-eyed ex-partner, Diego de Almagro.”

Visiting Lima’s Cerro San Cristóbal:

If you want to survey Lima and its surroundings much as General Quiso once did, then you can take a cab or a tour to the top of the hill. Much of what covers the hill now is one of Lima’s oldest shanty towns, so if you go in a cab, have the cab wait for you. There are also one-hour tours that leave from in front of Santo Domingo Church (on the first block of Jiron Camaná, downtown) that are run by Ofistur. Tours leaves every 15 minutes on Saturday and Sunday, from 10:00 A.M. to 9:00 P.M. and cost a couple of dollars. The tour crosses the Rimac River and spends about 20 minutes on the top of the hill. There is a small site museum and café up top and very good views on clear days.

(To be continued…)