Peru-Yale Machu Picchu Controversy Part 1

posted on May 7th, 2008 in Andes Mountains, Archaeology, Incas, Machu Picchu, Peru, Peru-Yale Controversy

In this and subsquent posts I’ll keep readers updated on the current controversy about the thousands of artifacts taken from the ancient Inca city of Machu Picchu in Peru nearly a century ago by the Yale historian, Hiram Bingham. Bingham “discovered” Machu Picchu in 1911 and, backed by the National Geographic Society, he returned with large expeditions in 1912 and 1914-1915. Each time, Bingham and his team shipped crates filled with archaeological discoveries to Yale from the now world-famous site. Yale is currently embroiled in an escalating dispute with Peru over the return of Bingham’s treasures, which are on display as part of the Yale’s permanent museum collection. Recently, a Peruvian team visiting Yale discovered that, far from the 5,000+ artifacts it was thought Bingham had acquired, Yale had more than 40,000 Machu Picchu artifacts–many of them still in unopened wooden crates that Bingham had shipped back. Peru is hoping to gain their return before the 100th anniversary of Bingham’s discovery of Machu Picchu in 2011. –Kim MacQuarrie

In this and subsquent posts I’ll keep readers updated on the current controversy about the thousands of artifacts taken from the ancient Inca city of Machu Picchu in Peru nearly a century ago by the Yale historian, Hiram Bingham. Bingham “discovered” Machu Picchu in 1911 and, backed by the National Geographic Society, he returned with large expeditions in 1912 and 1914-1915. Each time, Bingham and his team shipped crates filled with archaeological discoveries to Yale from the now world-famous site. Yale is currently embroiled in an escalating dispute with Peru over the return of Bingham’s treasures, which are on display as part of the Yale’s permanent museum collection. Recently, a Peruvian team visiting Yale discovered that, far from the 5,000+ artifacts it was thought Bingham had acquired, Yale had more than 40,000 Machu Picchu artifacts–many of them still in unopened wooden crates that Bingham had shipped back. Peru is hoping to gain their return before the 100th anniversary of Bingham’s discovery of Machu Picchu in 2011. –Kim MacQuarrie

(click below to read Part 1)

Finders Keepers?

After almost a century, Peru revives the drama of Hiram Bingham, 5,000 artifacts, and Machu Picchu.

By Christopher Heaney

Legal Affairs Magazine

March/April, 2006

In the 95 years since Machu Picchu was revealed to the world, the Inca citadel has become the most famous archaeological site in the Americas. It was only last July, however, that Peru gave it a museum worthy of its reputation. One had existed there for more than 40 years, about two miles below Machu Picchu, but it had lacked organization and, at one point, windows. Whole display cases were empty, and those that weren’t did not contain artifacts from the site. In 2004, however, Peru’s National Institute of Culture, or INC, and a young museum designer, Veronika Tupayachi, started remaking the museum as a tribute to the great pre-European monument, with explanations of the native engineering employed to construct it, computer-animated reenactments of the kind of sun worship that its creators practiced, and over 210 artifacts found by Peruvian archaeologists in Machu Picchu, or “old mountain” in Quechua.

But Tupayachi and the INC couldn’t work miracles. At the cedar-and-stone museum’s dedication ceremony last summer—officially, the Manuel Chávez Ballón Site Museum, named after one of the first Peruvian archaeologists to investigate the site—the INC’s regional director in nearby Cuzco, David Ugarte, praised the redesign but expressed concern about what the museum lacked: nearly 5,000 items excavated from Machu Picchu in 1912 by the American Hiram Bingham and housed ever since in Yale University’s Peabody Museum. At the time of the dedication, Peru and Yale had been negotiating over the artifacts for several years. Four months later, in November, Peru announced that it was prepared to sue Yale in the Connecticut courts to regain the artifacts. “What if Peru had George Washington’s things?” Ugarte explained in December. “We would have to return them. They would mean something to the United States, not Peru.”

Peru and Yale’s relationship was not always so adversarial. As Bingham once wrote to an editor, in time “a story can undergo very extraordinary changes not withstanding the honesty, integrity, and good intentions of the narrator.”

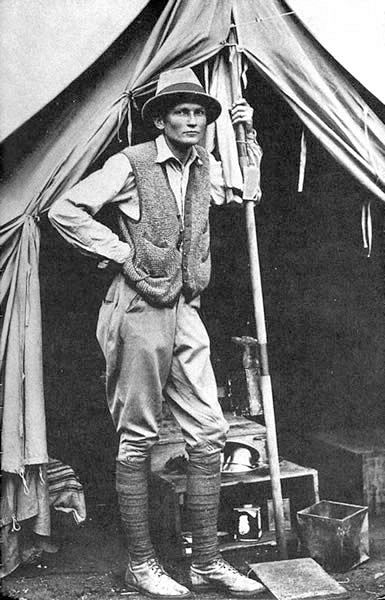

In July 1911, a Peruvian named Melchor Arteaga led Bingham up to ruins overgrown with the jungle beard of the Andean mountains. It was an age of exploration, and, as the director of an expedition from Yale, the tall, towheaded Bingham was chasing down the last, supposedly lost, cities of the Inca Empire. Bingham’s work in Peru was made easier by Peruvian President Augusto Leguía, who gave the expedition military escorts and letters of introduction, and by the business community, which provided free train passage and use of telegraph wires. Peru’s gentry and academics had set Bingham on Machu Picchu’s trail; he noted in his journal that a local farmer named Agustín Lizárraga was the ruin’s “discoverer” and that two families lived in the ruins.

Where others had seen rubble or tombs for looting, though, Bingham saw perfect white granite stonework and temples recalling the Incas’ oldest creation myths. The scion of famous Hawaiian missionaries, he had spent his childhood reading about explorers. At the time of his first trip to Machu Picchu, Bingham was 35, with a B.A. from Yale and a Ph.D. in history from Harvard, and he had taught at Berkeley, Harvard, Princeton, and Yale. He lived in the largest house in New Haven, Conn., with his wife, an heiress to the Tiffany jewelry fortune, and his six (soon to be seven) sons. Teaching had come to bore Bingham, however, and in 1906 he had first tried his hand as an explorer by following the marches of Simón Bolivar, “The Liberator” of South America. From 1908 to 1909, Bingham traced the old Spanish trade routes between Argentina and Peru and ran into two members of Butch Cassidy’s and the Sundance Kid’s gang along the way. He was, observed the modern explorer Hugh Thomson, a “rolling maul of enthusiasm and sheer drive.”

“My new Inca City, Machu Picchu . . . is unknown and will make a fine story,” Bingham wrote to his wife. He was no archaeologist, but he became a peerless promoter of Peru’s “lost cities,” ancient human remains, and dramatic Andean peaks on his return to the United States that fall. The U.S. press was especially excited by Machu Picchu; The New York Herald declared the ruins the most important and best preserved in South America. The discovery left “the theory that civilization was first brought to these shores in Spanish caravels in a ridiculous light,” The Christian Science Monitor declared.

Peruvian newspapers, however, were the first to understand that Bingham and Yale’s promotion of Machu Picchu would be an asset for tourism. “There is money in it for Peru,” the English-language West Coast Leader declared. Peru’s scientists applauded Yale’s expedition for providing Machu Picchu as evidence of the “grandeur of Peru’s ancient civilization,” and President Leguía encouraged Bingham by promising a 10-year concession giving Yale the exclusive right to carry on archaeological exploration in Peru.

Gilbert Grosvenor, the president and editor of National Geographic Magazine, spent $10,000 to send Bingham back to Peru the following summer, with the hope that he would be “able to excavate and bring back a shipload of antiquities for your museum at Yale.” Machu Picchu swarmed with activity. Bingham’s archaeological army of American topographers and Peruvian workers cleared jungle, mapped sacred plazas, and excavated what burials the looters hadn’t destroyed. Bingham took 700 photographs of the beautiful Inca temples and ceremonial baths. By November, nearly 1,600 artifacts—ranging from elegant ceramic jars to a silver headdress—and thousands of small potsherds and bone fragments were packed into crates bound for Yale.

But Yale’s scientific discovery of Machu Picchu in 1911 had so inspired Peruvian intellectuals that by 1912 they were loath to see its artifacts leave the country. Some declared that it would be the ultimate insult if Peruvians had to go to North America to study what was once in Peru. While Bingham and the expedition excavated Machu Picchu, the Peruvian parliament tabled the concession promised by President Leguía, putting the artifacts in limbo. Bingham rushed to Lima to fight for a “Supreme Resolution” from the government, allowing the artifacts to be exported to Yale. He received it in late October 1912, but with a condition: “The Peruvian Government reserves to itself the right to exact from Yale University and the National Geographic Society of the United States of America the return of the unique specimens and duplicates.”

With the Peruvian government’s permission, the crates set sail, and four weeks later arrived in New Haven. Bingham’s photographs and articles filled an entire issue of National Geographic Magazine and sparked international interest in Peru. The New York Times declared Machu Picchu the “Greatest Archaeological Discovery of the Age.”

Bingham and Yale returned to Peru in 1915 with a third expedition. While some members excavated other “lost cities” reached in 1911, Bingham visited Machu Picchu. He “nearly wept to see how it had gone back to jungle and brush,” he wrote to his wife, but did no further excavations before going on to map the 20-mile path rising to 13,780 vertical feet hiked today as the Inca Trail. Peru’s suspicion of foreign exploration had worsened, however, and Bingham was stung by local rumors that the expedition had returned to Machu Picchu with a “steam shovel from Panama in order for us to get out the treasure faster; that we had secured between 500,000 and 5 million dollars worth of Inca gold and were shipping it out of the country via Bolivia.” He proved the accusations false, and the expedition was eventually able to leave with artifacts it had excavated. Bingham was “relieved” when National Geographic cancelled future funding for expeditions in Peru and he told a friend, “I hope I may never have to go back to Peru.”

In 1917, Bingham left Yale to command the Allies’ largest flying school in World War I. Three years later, Peru’s consul in the U.S. requested the “original and duplicate objects taken from Peru,” citing the 1912 Supreme Resolution, which referred to the Machu Picchu artifacts. In 1921, Bingham sent back valueless potsherds and bones from 1915. None of the returned artifacts were from the 1912 Machu Picchu collection.

Since negotiations began several years ago, Yale has been Since negotiations began several years ago, Yale has been circumspect regarding Peru’s claim that Bingham and Yale violated the terms by which the Machu Picchu artifacts left the country. But after the South American nation threatened a lawsuit in November, the university made public its legal position: an 1852 Peruvian Civil Code which, according to Yale, was in effect at the time, “gave Yale title to the artifacts at the time of their excavation and ever since.” However, to preserve the “relationship between Yale and Peruvian scholars centered around study and education involving the Machu Picchu materials,” Yale offered to help return, install, and maintain a “substantial number” of artifacts for display and research in a museum in Machu Picchu or Cuzco. Peru, in turn, would recognize the contributions made by Yale during its nearly century-long stewardship of the collection.

Peru’s threatened lawsuit is an apparent rejection of Yale’s legal interpretation and the compromise it has proposed, though negotiations are ongoing. Diplomacy seems mainly to have been left to the Machu Picchu site museum, which credits Bingham, Yale, and National Geographic for promoting Machu Picchu and avoids addressing the Yale excavations head on.

In 1948, having become an active republican after World War I, and having served as lieutenant governor of Connecticut, briefly as its governor, and, for eight years, as a U.S. Senator from the state—the 72-year-old Bingham was putting the finishing touches on his final of three books on Machu Picchu when Peru invited him back as a guest of honor for a conference devoted to Pan-American indigenous culture. Resentments on both sides had softened over the years. National museum director Luis Valcárcel best exemplified the change in attitude toward Bingham and Yale. Valcárcel had once been Yale’s fiercest critic, but in 1941 he had traveled to the United States and visited Bingham in Washington, D.C., and the Machu Picchu collection at Yale. Yale had “an important attitude towards South America,” he reported in Peru afterwards.

While Bingham was en route to Peru, however, an even greater tribute was planned. Bingham was brought to Machu Picchu in October to dedicate a new tourist road that would give access to the citadel above. Visibly moved, according to the local newspaper El Comercio, the aged explorer received endless tributes from local intellectuals, government officials, and the U.S. Ambassador to Peru. The new “Hiram Bingham Highway,” the national government’s representative declared, would “again unite the prestige of the illustrious professor, Dr. Hiram Bingham, with the destiny of our country.”

Fifty-eight years later, the highway, still bearing Bingham’s name, connects the ruins above with the trains full of tourists below, and the Peruvian government’s new site museum of Machu Picchu in between.